Lewis Thomas (1913-1993) wrote in his essay Late Night Thoughts on Listening to Mahler’s Ninth Symphony,

“I cannot listen to the last movement of the Mahler Ninth without the door-smashing intrusion of a huge new thought: death everywhere, the dying of everything, the end of humanity…How do the young stand it? How can they keep their sanity? If I were very young, sixteen or seventeen years old, I think I would begin, perhaps very slowly and imperceptibly, to go crazy…If I were sixteen or seventeen years old…I would know for sure that the whole world was coming unhinged. I can remember with some clarity what it was like to be sixteen…I was in no hurry…The years stretched away forever ahead, forever…It never crossed my mind to wonder about the twenty-first century; it was just there, given, somewhere in the sure distance.”

Thomas was referring to the threat of nuclear war, which is still very much with us. Now, can you imagine as bad as the COVID-19 pandemic has been, what a nuclear war would be like? We need to rid our planet of these weapons, now.

As I was listening to the final movement of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 9, the Adagio, this past Monday, I was also thinking, of course, about the frightening ravages of COVID-19, but also climate change and the precipitous decline in biological diversity caused by humans. All of this is driven by the fact that there are too many people on the planet, and the answer is not to kill (by whatever means) people who are already here, but to bring fewer children into the world so we can lower human population to a sustainable level in the coming generations. We could all have a higher standard of living without trashing the planet.

On Wednesday, the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, PBS aired a new BBC documentary, Climate Change: The Facts. I was riveted by the program, presented by Sir David Attenborough, who will turn 94 next month the day before I turn 64. David Attenborough is an international treasure. Watching him so expertly present, as he always does, the urgency of this climate crisis and remembering his many outstanding documentary series such as Life on Earth and The Living Planet, I became teary eyed knowing that he will not be with us for very much longer. You wish someone like David Attenborough or Carl Sagan could live for hundreds of years. Because, when our life is over, we will cease to exist as a conscious entity, for all eternity. I am now certain of that. Realizing that this is our one and only life gives one a very different perspective on what we are doing to this world—and to each other. Humanists value the sanctity of each human life more than anyone who believes in an afterlife. Humanists fully understand the enormous responsibility each of us living in this current generation has to ensure that our civilization does not descend into a dystopian existence. There will be no salvation, just unimaginable pain, suffering, and destruction of all that is good, if we fail.

I am so inspired by young Greta Thunberg, who features prominently in the documentary. Greta and the many other young activists around the world give me hope for the future. Her words and conviction brought more tears to my eyes. I may be 63, but I’m with you 100%, Greta. Sign me up!

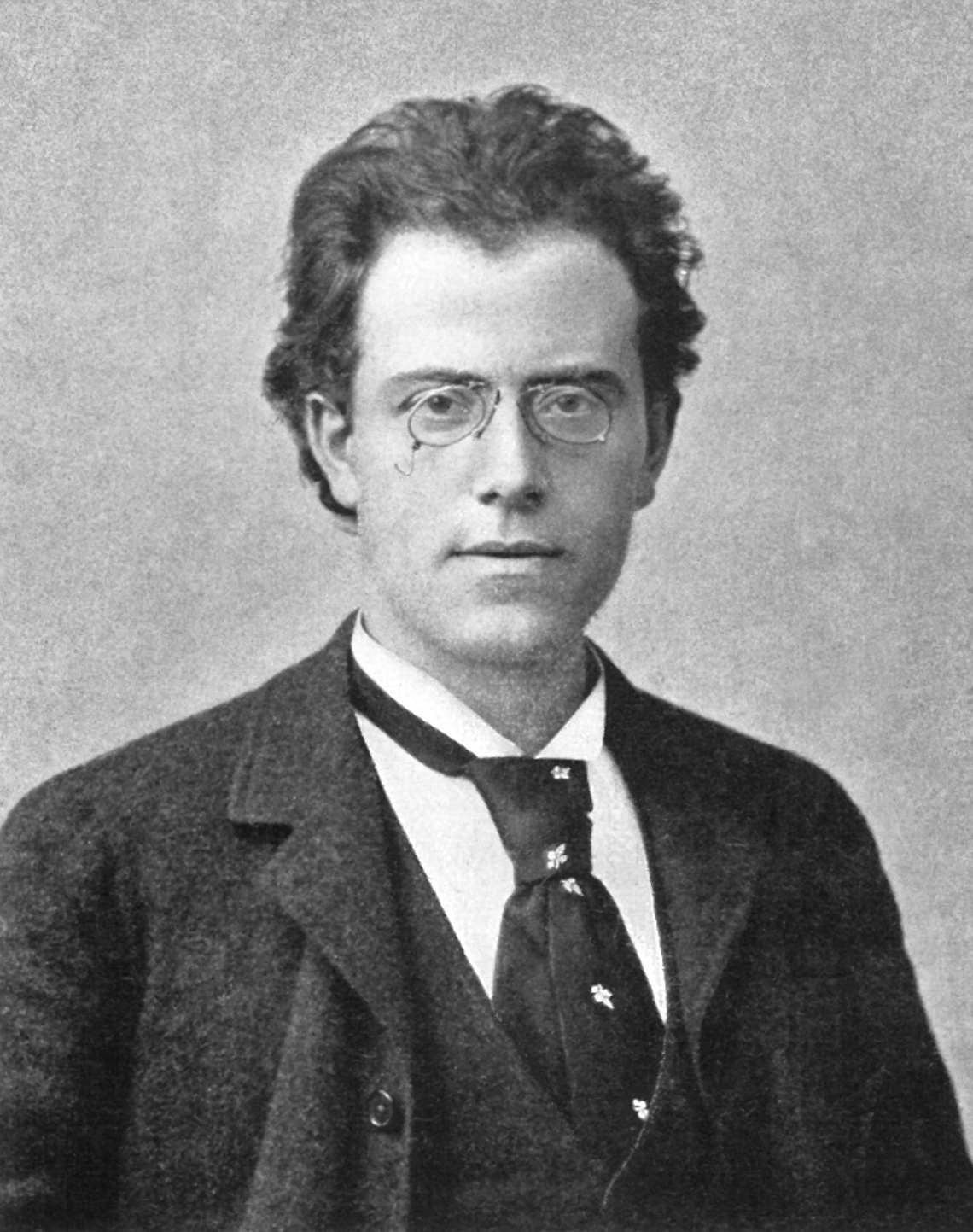

In 1908 and 1909, Gustav Mahler finished his last completed work, the Symphony No. 9. There was much turmoil and tragedy in Mahler’s life prior to the writing of this symphony. His beloved oldest daughter, Maria Anna Mahler, died of scarlet fever and diphtheria on 5 July 1907 at the age of 4. Immediately after Maria’s death, Mahler learned that he had a defective heart. And his relationship with his wife Alma had become strained. Gustav Mahler died on 18 May 1911. He never heard his Symphony No. 9 performed. It received its premiere on 26 June 1912 in Vienna with Bruno Walter conducting the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra.

The final movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 9, the Adagio, is one of the most moving pieces of music I have ever heard. While listening to it, one thinks of all the beauty that was and is in the world, and how terribly much we have lost.

The most expressive recording of the Adagio I have heard is by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir Georg Solti (Decca 473 274-2). If this movement of 24:37 does not bring you to tears, I don’t know what will.