We are so very fortunate here in southern Wisconsin to have evening public lectures the 2nd Tuesday every month of the year at the University of Wisconsin Space Place, expertly organized by Jim Lattis. On Tuesday, November 12th, Clif Cavanaugh (retired physics and astronomy professor at the UW in Richland Center) and I made the trek (as we often do) from Spring Green-Dodgeville to the Space Place in Madison. This month, we were treated to an excellent presentation by Keith Bechtol, an Observational Cosmologist in the Physics Department at UW-Madison. His topic was The Big Picture: Science with Astronomical Surveys. Keith is an early career scientist with a bright future. His presentation was outstanding.

I’d like to share with you some of the highlights.

Before the talk, which is mostly about the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), currently under construction in Chile and expected to see first light in 2020, I asked Keith about whether LSST would be renamed the Vera Rubin Telescope as was announced at AAS 234 in St. Louis this past summer. As it turns out, Keith has been a vocal advocate for naming LSST after Vera Rubin, though no final decision has yet been made.

Before I get into notes from the talk, I wanted to share with you the definition of the word synoptic in case you are not familiar with that word. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word synoptic as “furnishing a general view of some subject; spec. depicting or dealing with weather conditions over a large area at the same point in time.” But rather than the traditional meteorological definition, here we are referring to a wide-field survey of the entire night sky visible from Cerro Pachón in Chile, latitude 30˚ S.

Keith first talked about how astronomical imaging is currently advancing along two fronts. The first is high-resolution imaging, as recently illustrated with first image of the event horizon of a black hole from the Event Horizon Telescope, where an amazing resolution of around 25 microarcseconds was achieved.

In general, the larger the telescope aperture, the smaller the field of view.

A survey telescope, on the other hand, must be designed to cover a much larger area of the sky for each image.

Not only can a survey telescope detect “anything that changes” in the night sky, but it also allows us to probe the large-scale structure of our universe. Three still-mysterious entities that are known to affect this large-scale structure are dark energy, dark matter, and neutrinos. Keith indicates that “these names are placeholders for physics we don’t yet fully understand.”

Dark energy, which is responsible for driving galaxies apart at an accelerating rate, is unusual in that it maintains a constant density as the universe expands. And its density is very low.

Supernovae are a very useful tool to probe the dark-energy-induced accelerating expansion of the universe, but in any particular galaxy they are exceedingly rare, so by monitoring large areas of the sky (ideally, the entire sky), we can discover supernovae frequently.

The mass distribution of our universe subtly affects the alignment and shapes of distant galaxies through a phenomenon known as weak gravitational lensing. Understanding these distortions and correlations requires a statistical approach looking at many galaxies across large swaths of sky.

Closer to home, small galaxies that have come too close our Milky Way galaxy are pulled apart into stellar streams that require a “big picture” approach to discover and map. The dark matter distribution in our Milky Way galaxy plays an important role in shaping these stellar streams—our galaxy contains about ten times as much dark matter as normal matter.

With wide-field surveys, not only do we need to cover large areas of sky, but we also want to be able to see the faintest and most distant objects. That latter property is referred to as “going deeper”.

The LSST will provide a dramatic increase in light gathering power over previous survey instruments. The total number of photons collected by a survey instrument per unit time is known as the étendue, a French word, and it is the field of view (in square degrees) × the effective aperture (in m2) × the quantum efficiency (unitless fraction). The units of étendue are thus m2deg2. Note that the vertical axis in the graph below is logarithmic, so the LSST will have a significantly higher étendue than previous survey instruments.

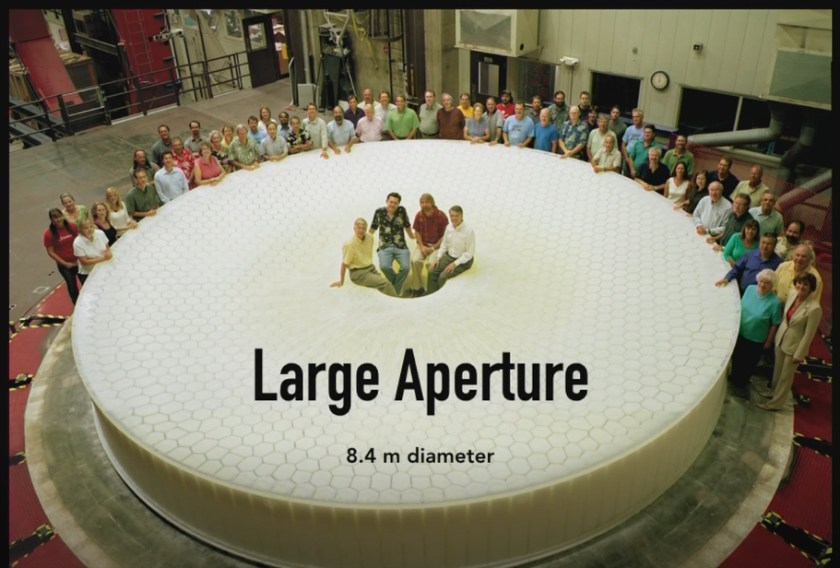

The largest monolithic mirrors in the world are fabricated at the Steward Observatory Mirror Lab at the University of Arizona in Tucson. The largest mirrors that can be produced there are 8.4 meters, and LSST has one of them.

Remember the Yerkes Observatory 40-inch refractor, completed in 1897? It has held the record as the largest lens ever used in an astronomical telescope. Until now. A 61.8-inch lens (L-1) and a 47.2-inch (L-2) have been fabricated for use in the LSST camera.

LSST will utilize a camera that is about the size of a car. It is the largest camera ever built for astronomy.

The LSST camera will produce 3.2 gigapixel images. You would need to cover about half a basketball court with 4K TV screens to display the image at full resolution.

An image will be produced every 15 seconds throughout the night, every clear night, and each patch of sky will be reimaged every three nights. That is a HUGE amount of data! ~10 Tb of data each night. Fiber optical cable will transport the data from Cerro Pachón to the National Center for Supercomputing Applications in Urbana, Illinois, where it will be prepared for immediate use and made publicly available to any interested researcher. The amount of data is so large that no one will be downloading raw data to their local computer. They will instead be logging in to the supercomputer and all processing of the data will be done there, using open source software packages.

There are many data processing challenges with LSST data needing to be solved. Airplane, satellite, and meteor trails will need to be carefully removed. Many images will be so densely packed with overlapping objects that special care will be needed separating the various objects.

One LSST slide that Keith presented showed “Solar System Objects: ~ 6 million” and that piqued my interest, given my ongoing research program of observing stellar occultations by asteroids and trans-Neptunian objects for IOTA. Currently, if you endeavor to observe the highest probability occultation events from a fixed observatory location each night, you will be lucky to record one positive event for every ten negative events (no occultation). The reason for this is that our knowledge of the orbital elements of the small bodies of the solar system is not yet precise enough to accurately predict where stellar occultation events will occur. Gaia DR3, scheduled for the latter half of 2021, should significantly improve the precision of small body orbits, and even though LSST does not have nearly the astrometric precision of Gaia, it will provide many valuable astrometric data points over time that can be used to refine orbital elements. Moreover, it is expected that LSST will discover—with its much larger aperture than Gaia—at least 10 times the number of asteroids and trans-Neptunian objects that are currently known.

During the question and answer period after the lecture, I asked Keith what effect the gigantic increase in the number of satellites in Earth orbit will have on LSST operations (global broadband internet services provided by organizations like SpaceX with its Starlink constellation). He stated that this definitely presents a data processing challenge that they are still working on.

An earlier version of Keith’s presentation can be found here. All images in this article except the first (OED) come from Keith’s presentation and have not been altered in any way.

References

Bechtol, Keith, “The Big Picture: Science with Astronomical Surveys” (lecture, University of Wisconsin Space Place, Madison, November 12, 2019).

Bechtol, Ellen & Keith, “The Big Picture: Science and Public Outreach with Astronomical Surveys” (lecture, Wednesday Night at the Lab, University of Wisconsin, Madison, April 17, 2019; University Place, Corporation for Public Broadcasting, PBS Wisconsin).

Jones, R. L., Jurić, M., & Ivezić, Ž. 2016, in IAU Symposium, Vol. 318, Asteroids: New Observations, New Models, ed. S. R. Chesley, A. Morbidelli, R. Jedicke, & D. Farnocchia, 282–292. https://arxiv.org/abs/1511.03199 .

Oxford English Dictionary Online, accessed November 17, 2019, https://www.oed.com/ .